I'm not going to waste my time writing a pseudo academic essay like I have in previous posts, but I'll take a stab at analyzing Shooting War's use of politically relevant material as a device for plot and style after the jump.

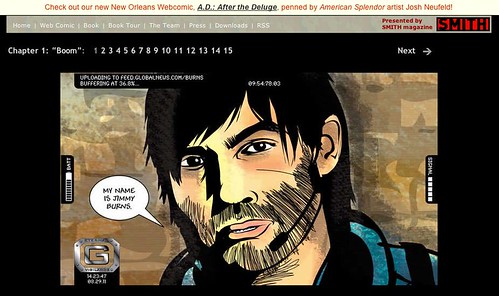

Shooting War is set in 2011, when John McCain is president and the war in Iraq has continued with no success or end in sight. The protagonist is Jimmy Burns, a renegade video blogger who has gained a name for shocking stories and footage. His catch phrase: "I have a knack for being in the right place when people are going to die." That line is worthy of Hombre or Fistful of Dollars, but I can only wish that it is meant to be read with at least some degree of irony. The plot of the book is pretty similar, if greatly lacking in originality, cohesiveness and continuity, of those seen in books coming out of the big houses, Marvel and DC, and imitates the edgy style of DC's Vertigo imprint (I am all too familiar with these plots after doing a soul crushing stint in the Marvel editorial department). Perhaps its difficulties with continuity in plot are due to its origination as a serialized web comic, but this does not forgive the confusing and lazy way a relatively straight forward plot is related. Time seems to progress forward randomly. The characters and dialog are extremely flat. I guess I've already told you that this is a bad book.

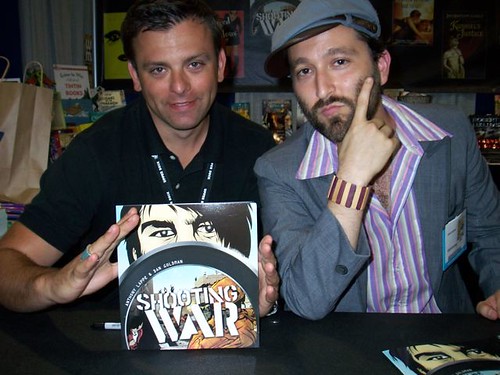

Apparently Lappe is the executive editor for the Guerrilla News Network's website, which I visited occasionally in high school, but found boring even then. Lappe is a little like Aliza Shvarts, who I discussed last post, in that he is clearly interested in being edgy, but seems unsure of how to do it. The politics of Shooting War aren't exactly ambiguous, but they are certainly incomplete and a bit over the top. In the conclusion, President McCain is so moved by the footage broadcast by Jimmy Burns of Iraqis being tortured that he decides to withdraw American soldiers. It seems like a joke, but the book doesn't end any other way. The combination of trendy liberal politics, trendy graphic art and absurd masculine fantasy, all of which seem incomplete in their conception, makes this work seem like even more of a get noticed quick scheme than Zeitgeist. What is sad is that the creators actually seem earnest in their efforts. But what can you expect from a couple of guys that look like this: