Apparently I haven't written anything on here since September. There are still some conspiracies that I want to talk about, but I've been working on this one 911 documentary that is pretty subpar, so I've had difficulty coming up with anything to say about it.

I did read this awesome Philip Roth book recently. It's not entirely relevant, but the plot does involve a couple conspiracy theories, which was cool.

The Plot Against America is kind of crazy book when you consider it in Roth's oeuvre. His work started as thinly veiled autobiography, and then moved to quite overt autobiography, that toyed with the reader's ability to interpret the autobiographical cues. Then he wrote a book called

The Facts, which is supposed to be an autobiography, but contains letters to Roth from fictional characters.

Operation Shylock took it a step further by placing Roth as a character in the middle of the Israeli conflict, and fucking a little bit with actual events.

The Plot Against America goes even farther by reinventing a significant period of American history in order to tell a fictional version of Roth's childhood, again with Philip Roth as the main character.

That subject could possibly be the subject of a dissertation that I will write in like a million years, but I'll quickly focus on the conspiracy aspects of the book.

So the basic premise of the book is that Charles Lindbergh, who was known in real life as a Nazi sympathizer, defeats FDR in the 1940 election on an anti-war platform (in reality Lindbergh was pushed to run, but didn't want to enter politics), at which point he signs a deal with Hitler and begins a veiled anti-Semitic Americanization program for minorities.

In the book, Philip Roth (who is eight at the time) is related to a famous Rabbi Bengelsdorf (not a real person) from Newark, who back Lindbergh and gets a position in his cabinet. As the novel reaches it's climax, Roth's Aunt Evelyn returns to Newark, and has to hide in the Roth's basement, because she fears that the government is after her, but Roth's parents won't let her in. The young Philip is the only one who knows of her hideout, and brings her food.

At this point there are two opposing conspiracy theories. One is that the Third Reich was responsible for the kidnapping of Lindbergh's son in 1932 (based on actual events) and used Charles Jr as leverage against Lindbergh, who they helped get into office and then used to set policy in America allowing them to conquer Europe before eventually taking over the United States as well. The second theory is that Bengelsdorf is a modern day Rasputin, who has mesmerized Lindbergh and controls him as part of an international Jewish conspiracy to rule the world.

The Bengelsdorf conspiracy echoes the New World Order conspiracy that you will find in more reactionary conspiracy media, which goes back to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and other absurdities of anti-Semitism.

The conspiracy involving Lindbergh's son is kind of cool, if totally implausible.

Neither of the theories are meant to hold any water in the book, and actually have little effect on the plot, but reflect the hysteria and paranoia that accompanies periods of political unrest. I think Roth captures the conpiracy theorists reasoning quite precisely.

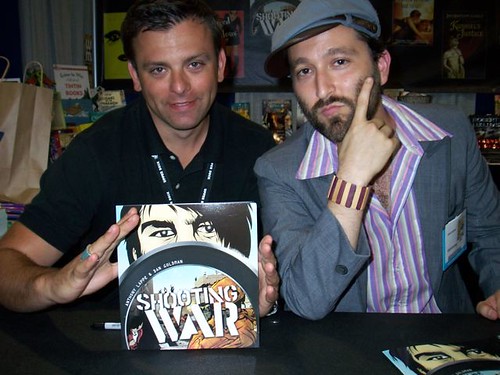

My Dad's Facebook picture.

My Dad's Facebook picture.

I started Jason Lutes'

I started Jason Lutes'